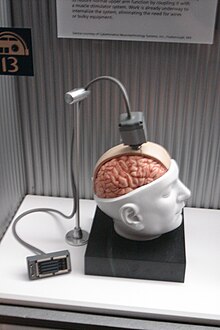

A brain–computer interface (BCI), often called a mind-machine interface (MMI), or sometimes called a direct neural interface or a brain–machine interface (BMI),

is a direct communication pathway between the brain and an external

device. BCIs are often directed at assisting, augmenting, or repairing

human cognitive or sensory-motor functions.

Research on BCIs began in the 1970s at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) under a grant from the National Science Foundation, followed by a contract from DARPA. The papers published after this research also mark the first appearance of the expression brain–computer interface in scientific literature.

The field of BCI research and development has since focused primarily on neuroprosthetics applications that aim at restoring damaged hearing, sight and movement. Thanks to the remarkable cortical plasticity of the brain, signals from implanted prostheses can, after adaptation, be handled by the brain like natural sensor or effector channels. Following years of animal experimentation, the first neuroprosthetic devices implanted in humans appeared in the mid-1990s.

Berger's first recording device was very rudimentary. He inserted silver wires under the scalps of his patients. These were later replaced by silver foils attached to the patients' head by rubber bandages. Berger connected these sensors to a Lippmann capillary electrometer, with disappointing results. More sophisticated measuring devices, such as the Siemens double-coil recording galvanometer, which displayed electric voltages as small as one ten thousandth of a volt, led to success.

Berger analyzed the interrelation of alternations in his EEG wave diagrams with brain diseases. EEGs permitted completely new possibilities for the research of human brain activities.

The difference between BCIs and neuroprosthetics is mostly in how the terms are used: neuroprosthetics typically connect the nervous system to a device, whereas BCIs usually connect the brain (or nervous system) with a computer system. Practical neuroprosthetics can be linked to any part of the nervous system—for example, peripheral nerves—while the term "BCI" usually designates a narrower class of systems which interface with the central nervous system.

The terms are sometimes, however, used interchangeably. Neuroprosthetics and BCIs seek to achieve the same aims, such as restoring sight, hearing, movement, ability to communicate, and even cognitive function. Both use similar experimental methods and surgical techniques.

In vision science, direct brain implants have been used to treat non-congenital (acquired) blindness. One of the first scientists to produce a working brain interface to restore sight was private researcher William Dobelle.

Dobelle's first prototype was implanted into "Jerry", a man blinded in adulthood, in 1978. A single-array BCI containing 68 electrodes was implanted onto Jerry’s visual cortex and succeeded in producing phosphenes, the sensation of seeing light. The system included cameras mounted on glasses to send signals to the implant. Initially, the implant allowed Jerry to see shades of grey in a limited field of vision at a low frame-rate. This also required him to be hooked up to a mainframe computer, but shrinking electronics and faster computers made his artificial eye more portable and now enable him to perform simple tasks unassisted.

In 2002, Jens Naumann, also blinded in adulthood, became the first in a series of 16 paying patients to receive Dobelle’s second generation implant, marking one of the earliest commercial uses of BCIs. The second generation device used a more sophisticated implant enabling better mapping of phosphenes into coherent vision. Phosphenes are spread out across the visual field in what researchers call "the starry-night effect". Immediately after his implant, Jens was able to use his imperfectly restored vision to drive an automobile slowly around the parking area of the research institute.

Researchers at Emory University in Atlanta, led by Philip Kennedy and Roy Bakay, were first to install a brain implant in a human that produced signals of high enough quality to simulate movement. Their patient, Johnny Ray (1944–2002), suffered from ‘locked-in syndrome’ after suffering a brain-stem stroke in 1997. Ray’s implant was installed in 1998 and he lived long enough to start working with the implant, eventually learning to control a computer cursor; he died in 2002 of a brain aneurysm.

Tetraplegic Matt Nagle became the first person to control an artificial hand using a BCI in 2005 as part of the first nine-month human trial of Cyberkinetics’s BrainGate chip-implant. Implanted in Nagle’s right precentral gyrus (area of the motor cortex for arm movement), the 96-electrode BrainGate implant allowed Nagle to control a robotic arm by thinking about moving his hand as well as a computer cursor, lights and TV.One year later, professor Jonathan Wolpaw received the prize of the Altran Foundation for Innovation to develop a Brain Computer Interface with electrodes located on the surface of the skull, instead of directly in the brain.

More recently, research teams led by the Braingate group at Brown University. and a group led by University of Pittsburgh Medical Center,both in collaborations with the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, have demonstrated further success in direct control of robotic prosthetic limbs with many degrees of freedom using direct connections to arrays of neurons in the motor cortex of patients with tetraplegia.

Electrocorticography (ECoG) measures the electrical activity of the brain taken from beneath the skull in a similar way to non-invasive electroencephalography (see below), but the electrodes are embedded in a thin plastic pad that is placed above the cortex, beneath the dura mater. ECoG technologies were first trialed in humans in 2004 by Eric Leuthardt and Daniel Moran from Washington University in St Louis. In a later trial, the researchers enabled a teenage boy to play Space Invaders using his ECoG implant.This research indicates that control is rapid, requires minimal training, and may be an ideal tradeoff with regards to signal fidelity and level of invasiveness.

(Note: these electrodes had not been implanted in the patient with the intention of developing a BCI. The patient had been suffering from severe epilepsy and the electrodes were temporarily implanted to help his physicians localize seizure foci; the BCI researchers simply took advantage of this.)

Signals can be either subdural or epidural, but are not taken from within the brain parenchyma itself. It has not been studied extensively until recently due to the limited access of subjects. Currently, the only manner to acquire the signal for study is through the use of patients requiring invasive monitoring for localization and resection of an epileptogenic focus.

ECoG is a very promising intermediate BCI modality because it has higher spatial resolution, better signal-to-noise ratio, wider frequency range, and less training requirements than scalp-recorded EEG, and at the same time has lower technical difficulty, lower clinical risk, and probably superior long-term stability than intracortical single-neuron recording. This feature profile and recent evidence of the high level of control with minimal training requirements shows potential for real world application for people with motor disabilities.

Light Reactive Imaging BCI devices are still in the realm of theory. These would involve implanting a laser inside the skull. The laser would be trained on a single neuron and the neuron's reflectance measured by a separate sensor. When the neuron fires, the laser light pattern and wavelengths it reflects would change slightly. This would allow researchers to monitor single neurons but require less contact with tissue and reduce the risk of scar-tissue build-up.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS CLICK THE LINK BELOW

LINK

Research on BCIs began in the 1970s at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) under a grant from the National Science Foundation, followed by a contract from DARPA. The papers published after this research also mark the first appearance of the expression brain–computer interface in scientific literature.

The field of BCI research and development has since focused primarily on neuroprosthetics applications that aim at restoring damaged hearing, sight and movement. Thanks to the remarkable cortical plasticity of the brain, signals from implanted prostheses can, after adaptation, be handled by the brain like natural sensor or effector channels. Following years of animal experimentation, the first neuroprosthetic devices implanted in humans appeared in the mid-1990s.

The history of brain–computer interfaces (BCIs)

The history of brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) starts with Hans Berger's discovery of the electrical activity of the human brain and the development of electroencephalography (EEG). In 1924 Berger was the first to record human brain activity by means of EEG. By analyzing EEG traces, Berger was able to identify oscillatory activity in the brain, such as the alpha wave (8–12 Hz), also known as Berger's wave.Berger's first recording device was very rudimentary. He inserted silver wires under the scalps of his patients. These were later replaced by silver foils attached to the patients' head by rubber bandages. Berger connected these sensors to a Lippmann capillary electrometer, with disappointing results. More sophisticated measuring devices, such as the Siemens double-coil recording galvanometer, which displayed electric voltages as small as one ten thousandth of a volt, led to success.

Berger analyzed the interrelation of alternations in his EEG wave diagrams with brain diseases. EEGs permitted completely new possibilities for the research of human brain activities.

BCI versus neuroprosthetics

Neuroprosthetics is an area of neuroscience concerned with neural prostheses. That is, using artificial devices to replace the function of impaired nervous systems and brain related problems, or of sensory organs. The most widely used neuroprosthetic device is the cochlear implant which, as of December 2010, had been implanted in approximately 220,000 people worldwide. There are also several neuroprosthetic devices that aim to restore vision, including retinal implants.The difference between BCIs and neuroprosthetics is mostly in how the terms are used: neuroprosthetics typically connect the nervous system to a device, whereas BCIs usually connect the brain (or nervous system) with a computer system. Practical neuroprosthetics can be linked to any part of the nervous system—for example, peripheral nerves—while the term "BCI" usually designates a narrower class of systems which interface with the central nervous system.

The terms are sometimes, however, used interchangeably. Neuroprosthetics and BCIs seek to achieve the same aims, such as restoring sight, hearing, movement, ability to communicate, and even cognitive function. Both use similar experimental methods and surgical techniques.

Human BCI research

Vision

Invasive BCI research has targeted repairing damaged sight and providing new functionality for people with paralysis. Invasive BCIs are implanted directly into the grey matter of the brain during neurosurgery. Because they lie in the grey matter, invasive devices produce the highest quality signals of BCI devices but are prone to scar-tissue build-up, causing the signal to become weaker, or even non-existent, as the body reacts to a foreign object in the brain.In vision science, direct brain implants have been used to treat non-congenital (acquired) blindness. One of the first scientists to produce a working brain interface to restore sight was private researcher William Dobelle.

Dobelle's first prototype was implanted into "Jerry", a man blinded in adulthood, in 1978. A single-array BCI containing 68 electrodes was implanted onto Jerry’s visual cortex and succeeded in producing phosphenes, the sensation of seeing light. The system included cameras mounted on glasses to send signals to the implant. Initially, the implant allowed Jerry to see shades of grey in a limited field of vision at a low frame-rate. This also required him to be hooked up to a mainframe computer, but shrinking electronics and faster computers made his artificial eye more portable and now enable him to perform simple tasks unassisted.

In 2002, Jens Naumann, also blinded in adulthood, became the first in a series of 16 paying patients to receive Dobelle’s second generation implant, marking one of the earliest commercial uses of BCIs. The second generation device used a more sophisticated implant enabling better mapping of phosphenes into coherent vision. Phosphenes are spread out across the visual field in what researchers call "the starry-night effect". Immediately after his implant, Jens was able to use his imperfectly restored vision to drive an automobile slowly around the parking area of the research institute.

Movement

BCIs focusing on motor neuroprosthetics aim to either restore movement in individuals with paralysis or provide devices to assist them, such as interfaces with computers or robot arms.Researchers at Emory University in Atlanta, led by Philip Kennedy and Roy Bakay, were first to install a brain implant in a human that produced signals of high enough quality to simulate movement. Their patient, Johnny Ray (1944–2002), suffered from ‘locked-in syndrome’ after suffering a brain-stem stroke in 1997. Ray’s implant was installed in 1998 and he lived long enough to start working with the implant, eventually learning to control a computer cursor; he died in 2002 of a brain aneurysm.

Tetraplegic Matt Nagle became the first person to control an artificial hand using a BCI in 2005 as part of the first nine-month human trial of Cyberkinetics’s BrainGate chip-implant. Implanted in Nagle’s right precentral gyrus (area of the motor cortex for arm movement), the 96-electrode BrainGate implant allowed Nagle to control a robotic arm by thinking about moving his hand as well as a computer cursor, lights and TV.One year later, professor Jonathan Wolpaw received the prize of the Altran Foundation for Innovation to develop a Brain Computer Interface with electrodes located on the surface of the skull, instead of directly in the brain.

More recently, research teams led by the Braingate group at Brown University. and a group led by University of Pittsburgh Medical Center,both in collaborations with the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, have demonstrated further success in direct control of robotic prosthetic limbs with many degrees of freedom using direct connections to arrays of neurons in the motor cortex of patients with tetraplegia.

Partially invasive BCIs

Partially invasive BCI devices are implanted inside the skull but rest outside the brain rather than within the grey matter. They produce better resolution signals than non-invasive BCIs where the bone tissue of the cranium deflects and deforms signals and have a lower risk of forming scar-tissue in the brain than fully invasive BCIs.Electrocorticography (ECoG) measures the electrical activity of the brain taken from beneath the skull in a similar way to non-invasive electroencephalography (see below), but the electrodes are embedded in a thin plastic pad that is placed above the cortex, beneath the dura mater. ECoG technologies were first trialed in humans in 2004 by Eric Leuthardt and Daniel Moran from Washington University in St Louis. In a later trial, the researchers enabled a teenage boy to play Space Invaders using his ECoG implant.This research indicates that control is rapid, requires minimal training, and may be an ideal tradeoff with regards to signal fidelity and level of invasiveness.

(Note: these electrodes had not been implanted in the patient with the intention of developing a BCI. The patient had been suffering from severe epilepsy and the electrodes were temporarily implanted to help his physicians localize seizure foci; the BCI researchers simply took advantage of this.)

Signals can be either subdural or epidural, but are not taken from within the brain parenchyma itself. It has not been studied extensively until recently due to the limited access of subjects. Currently, the only manner to acquire the signal for study is through the use of patients requiring invasive monitoring for localization and resection of an epileptogenic focus.

ECoG is a very promising intermediate BCI modality because it has higher spatial resolution, better signal-to-noise ratio, wider frequency range, and less training requirements than scalp-recorded EEG, and at the same time has lower technical difficulty, lower clinical risk, and probably superior long-term stability than intracortical single-neuron recording. This feature profile and recent evidence of the high level of control with minimal training requirements shows potential for real world application for people with motor disabilities.

Light Reactive Imaging BCI devices are still in the realm of theory. These would involve implanting a laser inside the skull. The laser would be trained on a single neuron and the neuron's reflectance measured by a separate sensor. When the neuron fires, the laser light pattern and wavelengths it reflects would change slightly. This would allow researchers to monitor single neurons but require less contact with tissue and reduce the risk of scar-tissue build-up.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS CLICK THE LINK BELOW

LINK

No comments:

Post a Comment